Researchers have come a long way in gaining an understanding of the many factors that can contribute to the development of obesity. One such factor that can cause weight gain or worsen obesity is stress, especially if we live in a state of ongoing day-to-day stress.

Obesity affects more than 40% of adults in the United States, and another 32% of adults have a diagnosis of overweight. Likely it’s no coincidence that the United States has both high rates of obesity and high rates of stress. Obesity is a chronic condition with a lot of complex hormonal processes at play, and stress is a factor that can also impact hormones that are related to our metabolic health.

Stress isn’t all bad, of course. It can be beneficial for keeping us safe and it can motivate us to meet an urgent work or school deadline. But when we have constant stress, the resulting ongoing hormonal changes can be harmful. Here we explore stress, how stress can impact weight over time, and what you can do to reduce chronic stress in your life.

Understanding Immediate vs Chronic Stress

If you’ve ever been in an almost fender-bender, you are all-too familiar with your immediate stress response. You probably felt your heart pounding and a rush of adrenaline as you quickly reacted to avoid the accident before you even realized what was about to happen.

This example shows how our stress response can be a good thing. It’s meant to keep us safe, especially in times of acute or immediate stress. Likely, right after the incident, you took a deep breath or sigh of relief and then went on with your day.

Now think about a time when you endured a longer experience of stress. Some examples include a breakup or divorce, the loss of a loved one, a long-distance move, or the fear that you might be let go at your job.

In these times, you may have experienced anxiety, a pit in your stomach, and more. Your stress response was doing its job. But that sigh of relief may not have come for quite some time, if at all. You were in a state of chronic stress.

Although these examples of chronic stress are more extreme, we can also experience chronic stress when many things compound in our everyday lives. For example, we might have a mix of family and work responsibilities, concerns with paying the rent or mortgage, relationship conflicts, and too many things on our to-do list and not enough time to do them. This mix of issues can create a cocktail of chronic stress.

We can also experience chronic stress from traumas we’ve endured in the past. Past trauma can cause us to be in a state of hypervigilance, a term used to describe constantly being subconsciously on high alert for a threat.

Understanding The Stress Response

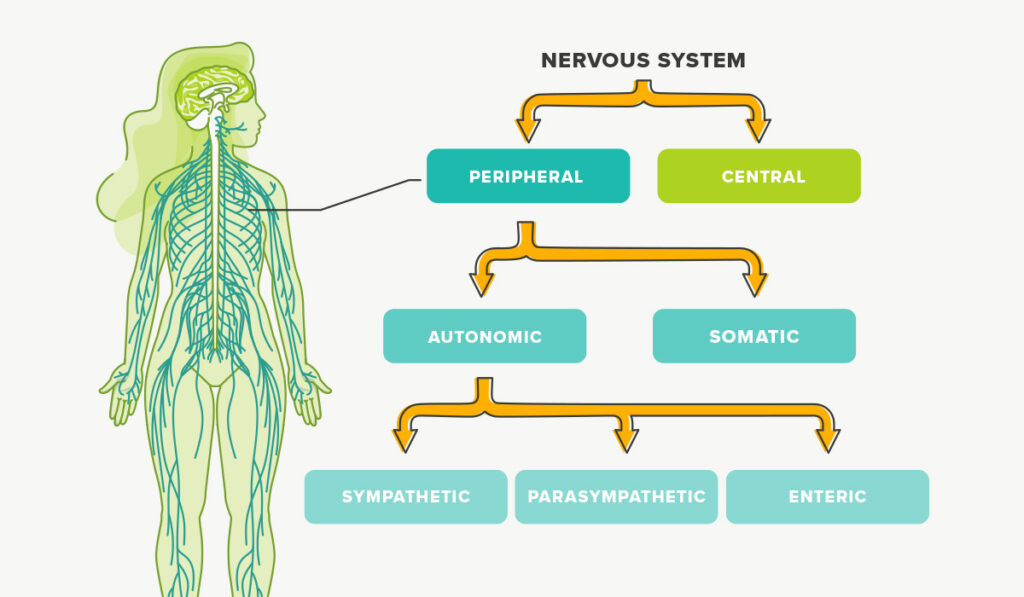

To understand stress, we must consider how our autonomic nervous system works. Our autonomic nervous system controls our involuntary responses, such as heart rate, body temperature, blood pressure, digestion, and more. It has three branches: the sympathetic nervous system, the parasympathetic nervous system, and the enteric nervous system.

The sympathetic nervous system controls our “fight-or-flight” response. The parasympathetic controls our “rest and digest” or calm response. And the enteric nervous system controls our GI tract.

In a nutshell, our fight-or-flight response is a survival mechanism. The stress response floods your bloodstream with stress hormones and stored glucose to give you the energy to react to an immediate threat. At the same time, the body directs all resources toward survival, so it halts or slows other unnecessary-in-the moment processes, like digestion.

Ages ago, our ancestors had to be wary of threats from predators, such as a charging mountain lion. Today, however, the near-fender bender example mentioned above is much more common when it comes to acute stress.

Once the immediate threat passes, the body generally goes back to its calmer state and usual functioning. However, if we experience chronic stress, our fight-or-flight response can get stuck in the “on” position, which can disrupt our neuroendocrine system and contribute to weight gain and obesity.

How The Stress Response Can Contribute To Obesity & Weight Gain

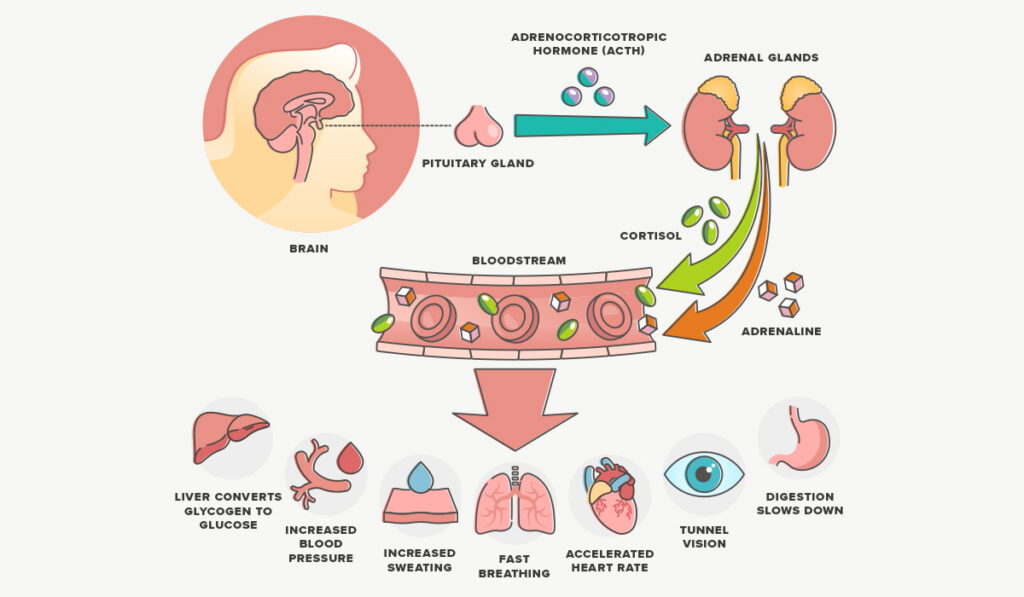

The immediate stress response starts in the brain, which then sends an alert to the adrenal glands to secrete glucocorticoids, or steroid hormones, including epinephrine, also known as adrenaline.

Adrenaline triggers the release of stored glucose and fats. This causes your blood sugar level to rise so that you have energy to respond to a threat. In our day-to-day lives, we aren’t typically sprinting away from predators. So we often don’t use up that excess glucose. Instead it sits in the bloodstream where it can cause issues.

If we are experiencing ongoing stress, the brain continues to send distress signals, which causes a hormonal cascade. The hypothalamus, a part of the brain, releases corticotropin-releasing hormone. This signals the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropin hormone. And this tells the adrenal gland to release cortisol. Cortisol increases production of glucose in the liver via what’s called gluconeogenesis. This helps keep glucose elevated in the bloodstream.

Insulin is a hormone produced in the pancreas that is required to get glucose out of your bloodstream and into your cells, where it can be converted to energy. But cortisol impairs insulin release and affects insulin’s ability to do its job, making us more insulin resistant. Insulin resistance over time can lead to obesity, and obesity also contributes to worsened insulin resistance.

Cortisol can also disrupt appetite signaling. It reduces the release of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). GLP-1 is an important hormone that, through various mechanisms, impacts other hormones that tell our brain we’re either hungry or full. For this reason, cortisol can contribute to overeating. And we may even engage in emotional eating, especially with comfort foods, to counteract negative feelings.

Cortisol also drives the accumulation of visceral fat. Visceral fat is the type that surrounds your organs and is associated with worsened health, including worsening insulin resistance, which can further contribute to obesity.

The stress response is designed for keeping us safe in an immediate threat. But you can see how chronic stress causes ongoing issues that disrupt hormones, contributing to weight gain and obesity. However, you’re not at the mercy of chronic stress.

What You Can Do To Reduce Chronic Stress

Remember that in addition to our fight-or-flight response, we also have our rest-and-digest response. These two responses generally work in opposition to each other. When we’re in fight-or-flight mode, all resources are directed toward our survival. So rest-and-digest mode is switched off.

If you can flip rest-and-digest mode back on, you can kill the switch on your fight-or-flight response. You can do this in several ways.

Try mindfulness practices. Meditation, yoga, or breathwork can help you tap back into rest-and-digest mode. These activities are great to practice regularly to strengthen your calm response. However, breathwork is an especially good tool to use when stress strikes, like when you need to calm yourself during an argument or before taking a test. The 6-6-5 method can do wonders when you’re facing a stressful moment.

Engage in regular physical activity. Exercise temporarily places your body under stress. Then when you stop, you get to relax. For this reason, exercise can be a great way to adapt to stress and strengthen your ability to toggle between stress and a calmer state. In short, physical activity increases your resilience to stress.

Prioritize quality nutrition. As much as possible, eliminate ultra-processed foods. These are foods that typically have a lot of added sugar, sodium, preservatives, and chemicals known as obesogens, which can further contribute to weight gain and obesity. Ultra-processed foods may even worsen stress. By fueling your body with whole foods, you’ll help ensure optimal nutrition, which supports your metabolism while also supporting your mental health.

Eat more omega-3 fatty acids. Omega-3s, found in fatty fish, avocado, and more, may help reduce stress by lowering inflammation and cortisol levels and helping the body recover.

Get good quality and quantity sleep. Sleep deprivation can ratchet up your stress level, so aim for at least seven hours of sleep per night, and try to minimize any interruptions from noise or light pollution. But getting good sleep can be easier said than done. Did you know diet can help?

Reduce the items on your to-do list. Chronic stress can creep up when we have too many responsibilities all at once. Look for ways to outsource or offload items on your to-do list, whether that’s outsourcing meals to a meal delivery service, hiring a cleaner, or just nixing tasks and commitments that aren’t immediate.

Take time for self-care. Often when we’re busy or chronically stressed, our self-care practices are the first thing to fall to the wayside. But in times of stress, you need self-care more than ever to help you engage your rest-and-digest system. The above tips are great ways to engage in self-care and ease stress at the same time.

Takeaway

Stress can cause a hormonal cascade that can lead to weight gain and obesity, which is a complex chronic condition. But stress doesn’t have to control your life or your body composition.

Understanding how the stress response works can help you take steps to counteract it when tough moments or days strike. Knowing how to turn off your fight-or-flight mode to achieve a calmer state can help.

About The Author: Jennifer Chesak, MSJ

Jennifer Chesak is an award-winning author, science and medical journalist, editor, and fact-checker, and her work has appeared in several national and international publications, including the Washington Post and BBC. Recently her debut nonfiction book on women’s health was awarded the IBPA Benjamin Franklin silver medal. Chesak earned her master of science in journalism from Northwestern University’s Medill. She currently teaches in the journalism and publishing programs at Belmont University, leads various workshops at the literary nonprofit The Porch, and serves as the managing editor for the literary magazine SHIFT. Find her work at jenniferchesak.com and follow her on socials @jenchesak.