Most people have an understanding that exercise is important for weight management, but the underlying reasons aren’t always so clear. That’s because of an outdated notion that the benefits of physical activity have to do with calorie burning. The truth is that calorie burning is only a small part of the equation.

A lack of movement has negative effects on your metabolic health and contributes to obesity. Conversely, engaging in a more active lifestyle has metabolic health benefits, including for weight management.

In this article, we’ll explore how physical activity boosts your overall metabolic health, how exercise reduces obesity risk, and the unique benefits of different types of exercise. The good news is that you don’t have to engage in extreme exercise styles or durations to reap the advantages.

Understanding the Complexity of Obesity

Outdated science and diet culture has long perpetuated the idea that weight management is about the easy math of calories-in-calories-out. The old idea was that weight loss was simply about burning more calories than you consume. Yes, calories matter to an extent. But weight management is about so much more than calories.

Metabolism, by definition, involves all the physical and chemical processes that turn food into energy. Complex hormonal and signaling processes are at play that impact our metabolism and therefore our weight. Metabolic health is how well or efficient the body performs these processes.

Factors that affect metabolism and weight:

How our bodies manage glucose (blood sugar) and insulin

Our levels of incretin, orexigenic, and other hormones that regulate hunger and fullness

Our levels of adipokines (cell signaling molecules released from fat cells)

Our body composition (such as body fat and lean mass percentages)

Our physical activity levels and types of exercise

Our diet

Our genetics

Our environment, including exposure to toxic chemicals known as obesogens

Exercise is one way we can modify some of these complex hormonal and signaling processes related to our metabolism and therefore improve our metabolic health.

Physical activity is a powerful tool, in conjunction with other lifestyle changes, that can help spur weight loss and reduce your risk for obesity. Different types of movement, such as cardio and strength training, have different beneficial effects, and we dive into those below. But first, understanding the benefits of physical activity requires an understanding of how our bodies manage blood sugar and insulin.

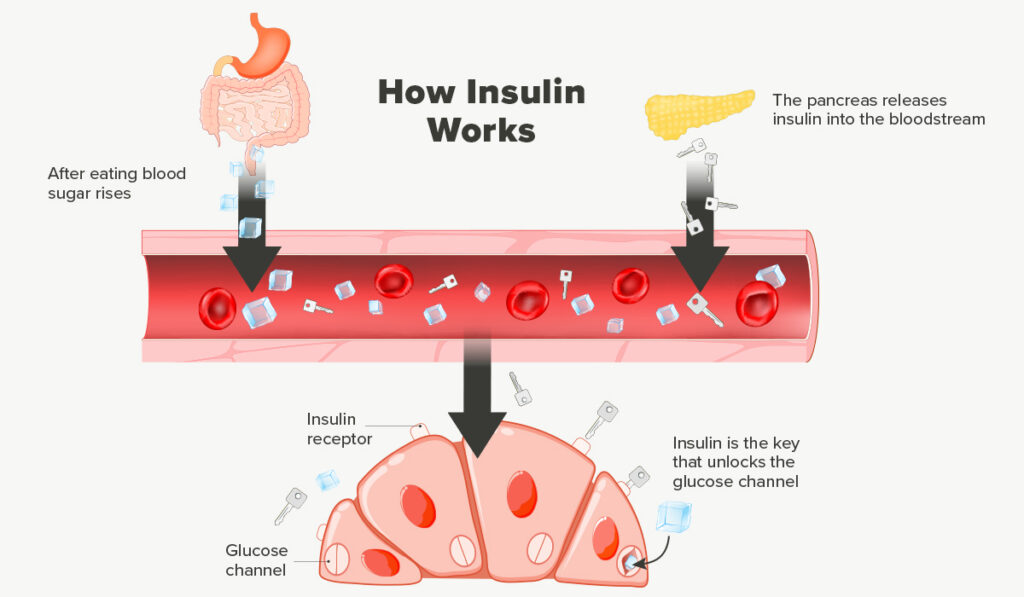

In response to glucose entering the bloodstream after we eat, the beta cells in our pancreas release insulin. Insulin is a hormone that signals to our cells to let glucose in so our cells can convert that glucose to our body’s universal energy currency called adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

If we are insulin sensitive, that means that our insulin response is working well. If we are insulin resistant, that means our cells have become resistant to insulin’s signaling. Insulin resistance occurs when our blood sugar has repeatedly spiked too high, requiring our pancreas to work harder to release more insulin to get the glucose out of the bloodstream and into cells. Over time, our cells essentially say “no” to more glucose. As a result, glucose and insulin levels remain high. Insulin promotes excess glucose to be stored as fat.

Insulin resistance and obesity are linked. Over time, insulin resistance can lead to prediabetes and Type 2 diabetes and increase one’s risk for cardiovascular and other chronic diseases. We can improve our insulin sensitivity via physical activity.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends engaging in 150 minutes of low to moderate intensity cardiovascular exercise per week. Walking, going for an easy bike ride, or doing water aerobics are all examples of moderate physical activity. If you’re working out at a vigorous intensity, the minimum is 75 minutes. Vigorous activities include running, swimming, cycling, rowing, etc. The CDC also recommends including full-body strength training at least twice a week.

How Cardio Reduces Risk for Obesity

Cardiovascular exercise helps our bodies become more efficient at using glucose and insulin in a few different ways.

When we exercise, we burn energy. Our body decides what fuel we are burning (typically glucose or fat) based on the exercise intensity and duration and whether we have recently eaten. But the key thing to know is that cardio helps us burn excess glucose and fat.

Cardio also helps our cells uptake glucose without the need for insulin release. Remember that high insulin levels contribute to fat storage, so the more we can get glucose into cells without requiring insulin, the better. During exercise, our bodies can uptake up to 50 times more glucose than when we’re not active. And after exercise, our insulin sensitivity is boosted for 48 hours.

Cardio exercise also increases our mitochondria (the powerhouse of cells) and their functioning. When we have more mitochondria that function well, we have better metabolic health and reduce our risk for obesity and related diseases. Plus, our bodies become more efficient at turning the foods we eat into usable energy.

As a bonus, cardio also suppresses our appetite in a few different ways. Animal studies show that exercise promotes the formation of a hybrid molecule called lac-phe. It’s a combination of two molecules: lactate and phenylalanine. Lac-phe seems to blunt appetite. Additionally, high intensity cardio (think sprint intervals, powerlifting, and more) reduces ghrelin, the “hunger hormone.”

Tips:

Get clearance. Check with your doctor before starting a new exercise routine, especially if you’ve been sedentary for a while or have dealt with an injury.

Start easy and slow. If you’re new to exercise, start out with an easy activity, such as walking. Increase your duration and speed slowly over time as you gain fitness. Eventually you may find that you’re ready to progress to other activities.

Spread movement throughout your day. You don’t have to block out an hour for exercise. A 15-minute walk here and there does wonders.

Walk after meals. Research shows that walking after a meal helps lower blood sugar and insulin, which can help counteract obesity.

Find activities you enjoy. Whether you like pickleball or power yoga, doing workouts you love will help keep your motivation up.

Avoid the all-or-nothing mentality. Any exercise is better than none. So if you can’t get in 150 minutes in per week, aim for what you can.

Try a HIIT workout. High-intensity interval training involves alternating periods of high intensity with lower intensity or even rest over the course of a workout. HIIT is great for maximizing your time since you’ll do shorter durations, and it reduces appetite. Just avoid doing HIIT every day.

Get some Zone 2 exercise. Zone 2 exercise involves activity done at 60% to 70% of your maximum heart rate. A good rule of thumb is that you should still be able to have a conversation and not be breathless. When performed for longer than 20 minutes, Zone 2 exercise increases mitochondria and insulin sensitivity.

How Strength Training Reduces Risk for Obesity

Strength training does wonders for the body and its metabolic health. You can strength train using weight-lifting machines, barbells or free weights, or by completing body-weight exercises, such as pushups, planks, squats, lunges, sit-ups, and more.

We lose muscle mass as we age, which changes our body composition. When we lose muscle, it’s not converted to fat, but we often end up gaining fat as a result, contributing to obesity. Adding and preserving muscle mass helps us counteract or reverse obesity in several ways.

Think of muscle as a sponge for glucose. Our muscles store glucose in the form of glycogen for later use. Exercise taps into those glycogen stores, so our muscles need to replenish themselves. In response to exercise, they can uptake glucose without the need for insulin. Muscle mass ultimately helps increase our insulin sensitivity.

Strength training also helps your existing fat tissue release adiponectin, a hormone and adipokine protein. Adiponectin increases insulin sensitivity and has anti-inflammatory effects.

More muscle mass can also increase our resting metabolic rate, or the number of calories we burn at rest. Ten weeks of resistance training, research shows, can boost your metabolic rate by 7%.

Some research also indicates that strength training may decrease ghrelin, the hunger hormone, and increase glucagon peptide-1 (GLP-1), which also helps reduce appetite.

Tips:

Get clearance. Check with your doctor before starting a new exercise routine, especially if you’ve been sedentary for a while or have dealt with an injury.

Try a few personal training sessions. Have a personal trainer set you up with a strength-training routine and teach you proper form.

Start with light weights. If you’re just getting started, use the first week or so to get acquainted with the moves and form before adding heavier resistance.

Focus on progressive overload. Progressive overload involves adding more reps or more weight over time to foster muscle gains. A good rule of thumb is to work your muscles until you can’t perform any more reps with proper form.

Get plenty of protein. Your muscles require protein for muscle protein synthesis. Per day, you need at least 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of bodyweight, but if you’re strength training, you might want to aim for more.

Takeaway

Physical activity is crucial for supporting our metabolism and overall metabolic health. It helps reduce our risk for obesity and aids in weight management. Obesity is a chronic condition, however, and physical activity is just one tool in the tool box.

You can further support the benefits you’re getting from more movement by also focusing on optimal nutrition. Reduce intake of ultra-processed foods, refined carbohydrates, and added sugars. Focus on whole foods, healthy fats, and adequate protein. You got this!

About The Author: Jennifer Chesak, MSJ

Jennifer Chesak is an award-winning author, science and medical journalist, editor, and fact-checker, and her work has appeared in several national and international publications, including the Washington Post and BBC. Recently her debut nonfiction book on women’s health was awarded the IBPA Benjamin Franklin silver medal. Chesak earned her master of science in journalism from Northwestern University’s Medill. She currently teaches in the journalism and publishing programs at Belmont University, leads various workshops at the literary nonprofit The Porch, and serves as the managing editor for the literary magazine SHIFT. Find her work at jenniferchesak.com and follow her on socials @jenchesak.